Geology of India

The geology of India started with the geological evolution of rest of the Earth i.e. 4.57 Ga (billion years ago). India has a diverse geology. Different regions in India contain rocks of all types belonging to different geologic periods. Some of the rocks are badly deformed and transmuted while others are recently deposited alluvium that has yet to undergo diagenesis. Mineral deposits of great variety are found in the subcontinent in huge quantity. Even the fossil records are impressive in which stromatolites, invertebrates, vertebrates and plant fossils are included. India's geographical land area can be classified into- Deccan trap , Gondwana and Vindhyan.

Firstly, the Deccan Trap covers almost all of Maharashtra, a part of Gujarat, Karnataka, Madhya Pradesh and Andhra Pradesh marginally. It is believed that the Deccan Trap was formed as result of sub-aerial volcanic activity associated with the continental deviation in this part of the Earth during the Mesozoic era. That is why the rocks found in this region are generally igneous type.

During its journey northward after breaking off from the rest of Gondwana, the Indian Plate passed over a geologic hotspot, the Réunion hotspot, which caused extensive melting underneath the Indian craton. The melting broke through the surface of the craton in a massive flood basalt event, creating what is known as the Deccan Traps. It is also thought that the Reunion hotspot caused the separation of Madagascar and India.

The Gondwana and Vindhyan include within its fold parts of Madhya Pradesh, Chhattisgarh, Orissa, Bihar, West Bengal, Andhra Pradesh, Maharashtra, Jammu and Kashmir, Punjab, Himachal Pradesh, Rajasthan and Uttaranchal.

The Gondwana Supergroup forms a unique sequence of fluviatile rocks deposited in Permo-Carboniferous time. Damodar and Sone river valley and Rajmahal hills in the eastern India are depository of the Gondwana rocks.

Contents |

Plate tectonics

The Indian craton was once part of the supercontinent of Pangaea. At that time, it was attached to Madagascar and southern Africa on the south west coast, and Australia along the east coast. 160 Ma (ICS 2004) during the Jurassic Period, rifting caused Pangaea to break apart into two supercontinents namely, Gondwana (to the south) and Laurasia (to the north). The Indian craton remained attached to Gondwana, until the supercontinent began to rift apart about in the early Cretaceous, about 125 Ma (ICS 2004). The Indian Plate then drifted northward toward the Eurasian Plate, at a pace that is the fastest movement of any known plate. It is generally believed that the Indian plate separated from Madagascar about 90 Ma (ICS 2004), however some biogeographical and geological evidence suggests that the connection between Madagascar and Africa was retained at the time when the Indian plate collided with the Eurasian Plate about 50 Ma (ICS 2004).[1] This orogeny, which is continuing today, is related to closure of the Tethys Ocean. The closure of this ocean which created the Alps in Europe, and the Caucasus range in western Asia, created Himalaya Mountains and the Tibetan Plateau in South Asia. The current orogenic event is causing parts of the Asian continent to deform westward and eastward on either side of the orogeny. Concurrently with this collision, the Indian Plate sutured on to the adjacent Australian Plate, forming a new larger plate, the Indo-Australian Plate.

- Tectonic evolution

The earliest phase of tectonic evolution was marked by the cooling and solidification of the upper crust of the earth surface in the Archaean era (prior to 2.5 billion years) which is represented by the exposure of gneisses and granites especially on the Peninsula. These form the core of the Indian craton. The Aravalli Range is the remnant of an early Proterozoic orogen called the Aravali-Delhi orogen that joined the two older segments that make up the Indian craton. It extends approximately 500 kilometres (311 mi) from its northern end to isolated hills and rocky ridges into Haryana, ending near Delhi.

Minor igneous intrusions, deformation (folding and faulting) and subsequent metamorphism of the Aravalli Mountains represent the main phase of orogenesis. The erosion of the mountains, and further deformation of the sediments of the Dharwaian group (Bijawars) marks the second phase. The volcanic activities and intrusions, associated with this second phase are recorded in composition of these sediments.

Early to Late Proterozoic calcareous and arenaceous deposits, which correspond to humid and semi-arid climatic regimes, were deposited the Cuddapah and Vindhyan basins. These basins which border or lie within the existing crystalline basement, were uplifted during the Cambrian (500 Ma (ICS 2004)). The sediments are generally undeformed and have in many places preserved their original horizontal stratification. The Vindhyans are believed to have been deposited between ~1700 and 650 Ma (ICS 2004).[2]

Early Paleozoic rocks are found in the Himalayas and consist of southerly derived sediments eroded from the crystalline craton and deposited on the Indian platform.

In the Late Paleozoic, Permo-Carboniferous glaciations left extensive glacio-fluvial deposits across central India, in new basins created by sag/normal faulting. These tillites and glacially derived sediments are designated the Gondwanas series. The sediments are overlain by rocks resulting from a Permian marine transgression (270 Ma (ICS 2004)).

The late Paleozoic coincided with the deformation and drift of the Gondwana supercontinent. To this drift, the uplift of the Vindhyan sediments and the deposition of northern peripheral sediments in the Himalayan Sea, can be attributed.

During the Jurassic, as Pangea began to rift apart, large grabens formed in central India filling with Upper Jurassic and Lower Cretaceous sandstones and conglomerates.

By the Late Cretaceous India had separated from Australia and Africa and was moving northward towards Asia. At this time, prior to the Deccan eruptions, uplift in southern India resulted in sedimentation in the adjacent nascent Indian Ocean. Exposures of these rocks occur along the south Indian coast at Pondicherry and in Tamil Nadu.

At the close of the Mesozoic one of the greatest volcanic eruptions in earths history occurred, the Deccan lava flows. Covering more than 500,000 square kilometres (193,051 sq mi) area, these mark the final break from Gondwana.

In the early Tertiary, the first phase of the Himalayan orogeny, the Karakoram phase occurred. The Himalayan orogeny has continued to the present day.

Major rock groups

Precambrian super-eon

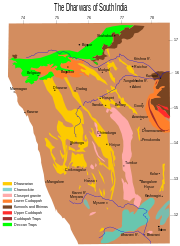

A considerable area of peninsular India, the Indian Shield, consists of Archean gneisses and schists which are the oldest rocks found in India. The Precambrian rocks of India have been classified into two systems, namely the Dharwar system and the Archaean system.

The rocks of the Dharwar system are mainly sedimentary in origin, and occur in narrow elongated synclines resting on the gneisses found in Bellary district, Mysore and the Aravalis of Rajputana. These rocks are enriched in Manganese and Iron ore which represents a significant resource of these metals. They are also extensively mineralized with gold most notably the Kolar gold mines located in Kolar. In the north and west of India, the Vaikrita system, which occurs in Hundes, Kumaon and Spiti areas, the Dailing series in Sikkim and the Shillong series in Assam are believed to be of the same age as the Dharwar system.

The metamorphic basement consists of gneisses which are further classified into the Bengal gneiss, the Bundelkhand gneiss and the Nilgiri gneiss. The Nilgiri system comprises Charnockites ranging from granites to gabbros.

Phanerozoic

- Palaeozoic

- Lower Paleozoic- Rocks of the earliest Cambrian period are found in the Salt range in Punjab and the Spiti are in central Himalayas and consist of a thick sequence of fossiliferous sediments. In the Salt range, the stratigraphy starts with the Salt Pseudomorph zone, which has a thickness of 450 feet (137 m) and consists of dolomites and sandstones. It is overlain by magnesian sandstones with a thickness of 250 feet (76 m), similar to the underlying dolomites. These sandstones have very few fossils. Overlying the sandstones is the Neobolus Shale, which is composed of dark shales with a thickness of 100 feet (30 m). Finally there is a zone consisting of red or purple sandstones having a thickness of 250 feet (76 m) to 400 feet (122 m) called the Purple Sandstone. These are unfossiliferous and show sun-cracks and worm burrows which is typical of subaerial weathering. The deposits in Spiti are known as Haimanta system and they consist of Slates, micaceous quartzite and dolomitic limestones. The Ordovician rocks comprise flaggy shales, limestones, red quartzites, quartzites, sandstones and conglomerates. Siliceous limestones belonging to the Silurian overlie the Ordovician rocks. These limestones are in turn overlain by white quartzite and this is known as Muth quartzite. Silurian rocks which contain typical Silurian fauna are also found in the Vihi district of Kashmir.

- Upper Paleozoic- Devonian fossils and corals are found in grey limestone in the central Himalayas and in black limestone in the Chitral area. The Carboniferous is composed of two distinct sequences, the upper Carboniferous Po, and the lower Carboniferous Lipak. Fossils of Brachiopods and some Trilobites are found in the calcareous and sandy rocks of the Lipak series. The Syringothyris limestone in Kashmir also belongs to the Lipak. The Po series overlies the Lipak series, and the Fenestella shales are interbedded within a sequence of quartzites and dark shales. In many places Carboniferous strata are overlaid by grey agglomeratic slates, believed to be of volcanic origin. Many genera of productids are found in the limestones of the Permo - Triassic, which has led to these rocks being referred to as "productus limestone". This limestone is of marine origin and is divided into three distinct litho-stratigraphic units based on the productus chronology: the Late Permian Chideru, which contains many ammonites, the Late - Middle Permain Virgal, and the Middle Permian Amb unit.

- Mesozoic

In the Triassic the Ceratite beds, named after the ammonite ceratite, consist of arenaceous limestones, calcerous sandstones and marls. The Jurassic consists of two distinct units. The Kioto limestone, extends from the lower the middle Jurassic with a thickness 2,000 feet (610 m) to 3,000 feet (914 m). The upper Jurassic is represented by the Spiti black shales, and stretches from the Karakoram to Sikkim. Cretaceous rocks are cover an extensive area in India. In South India, the sedimentary rocks are divided into four stages; the Niniyur, the Ariyalur, the Trichinopoly, and the Utatur stages. In the Utatur stage the rocks host phosphatic nodules, which constitute an important source of phosphates in the country. In the central provinces, the well developed beds of Lameta contain fossil records which are helpful in estimating the age of the Deccan Traps. This sequence of basaltic rocks was formed near the end of the Cretaceous period due to volcanic activity. These lava flows occupy an area of 200,000 square miles. These rocks are a source of high quality building stone and also provide a very fertile clayey loam, particularly suited to cotton cultivation.

- Cenozoic

- Tertiary period- In this period the Himalayan orogeny began, and the volcanism associated with the Deccan Traps continued. The rocks of this era have valuable deposits of petroleum and coal. Sandstones of Eocene age are found in Punjab, which grade into chalky limestones with oil seepages. Further north the rocks found in the Simla area are divided into three series, the Sabathu series consisting of grey and red shales, the Dagshai series comprising bright red clays and the Kasauli series comprising sandstones. Towards the east in Assam, Nummulitic limestone is found in the Khasi hills. Oil is associated with these rocks of the Oligo-Miocene age. Along the foothills of the Himilayas the Siwalik molasse is composed of sandstones, conglomerates and shales with thicknesses of 16,000 feet (4,877 m) to 20,000 feet (6,096 m) and ranging from Eocene to Pliocene. These rocks are famous for their rich fossil vertebrate fauna including many fossil hominoids.

- Quaternary period- The alluvium which is found in the Indo-Gangetic plain belongs to this era. It was eroded from the Himalayas by the rivers and the monsoons. These alluvial deposits consist of clay, loam, silt etc. and are divided into the older alluvium and the newer alluvium. The older alluvium is called Bhangar and is present in the ground above the flood level of the rivers. Khaddar or newer alluvium is confined to the river channels and their flood plains. This region has some of the most fertile soil found in the country as new silt is continually laid down by the rivers every year.

See also

- Indian Plate

References

- Trans. Min. Geology Institute India, 1, 47 (1906).

- Rec. Geology Survey India, 69, 109 and 458 (1935).

- Mem. Geology Survey India, 70 (1936 and 1940).

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||